GHOSTS:

Fragments, or faint echoes.

Or a memory without sound.

A vaporous movement in the corner of your eye.

A shadow.

Something left behind.

Or a moment broken off, something unseen, hesitant to leave.

And stillness.

A Log Entry From Truk Lagoon

My friend, Ito, said to look for ghosts. No one else thought to be so specific. Their advice was all the usual: be safe, have a good time, don't forget your sun block.

This was never thought of as an expedition. We weren't out to be the first at anything or discover the undiscovered. We just wanted to dive a little deeper, do something a little crazy in some exotic, warm, and isolated place.

We formed a simple plan: get some friends together, go to Truk Lagoon, dive the deep wrecks. Hit some of shallow ones, sure, but go for the deep ones--170 feet, or better. The San Francisco Maru sits on the bottom at 210. There are three Japanese army tanks on her decks at 175. There would be more than enough deep wrecks for us, waiting for any adventure we might choose.

There would be, at least, one big rule. Everyone had to really be comfortable with decompression diving in a remote location, hours by plane from any real medical assistance. And, of course, long, slow time underwater.

It would figure that amid the dozens of South Pacific destinations, in the middle of thousands of square miles of remote blue ocean, ghosts are not what most people would be looking for. Out here, the ocean itself is the magnet that draws. People usually come to witness the great miracle of Nature where everything lines up in perfect balance--a little rain, a little sun, a warm day turning into warm night--each day just enough different from the all others....

Day slowly turning into day after day.

A year of pleasant variations on a recurring theme.

Growing up near the Pacific after W.W.II, I saw visions of faraway places come in with the seas and swirl around the boilers off the Southern California cliffs. There was always a chance to dream of adventure, while standing along the coast.

There were constant reminders of the recent war then. There were Navy ships in the harbor, movies, news stories and documentaries on TV. There were the trophies in fathers' closets, the proud sons in military schools. But, there lingered a sense of something else--almost a tint that colored the air; a dark unseen impression that filtered our view of the passing time, and if you listened, an intangible, reverberating tone left ringing somewhere just beyond.

There were A-bomb tests conducted on some other far away tiny Pacific islands. The U.S. was a new power in the world. America was born again. Japan dug itself out of humiliation. We were all busy getting on with things. The fifties, the sixties....And, little, sleepy Truk Lagoon, hidden away on the other side of the world, recovered in its own way.

The trees grew back and finally divers discovered its hidden world.

I remember some theory about the advancement of civilization being favored by temperate climates; the change of seasons considered a catalyst to focus thought and activity. The tropics neither offer the need for clever architecture nor a solitary room to gather together ones thoughts. Here, everything is suspended in the sleepy gel of constancy and humidity. A sane man would stick to things like fishing and trying not to get hit by falling coconuts.

Lulled by the white noise lapping of lazy waves along the sand, stretched out in a perpetual hammock-induced haze of afternoon naps and gentle breezes; energy is the one thing lacking here. It takes much too much effort to plan for war, cut down hillsides, pave runways, stockpile munitions, supplies, equipment, and men. Thousands of men.

You'd have to be insane.

Still, out here, in this sleepy paradise, is a hidden domain of ghosts.

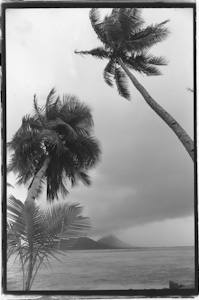

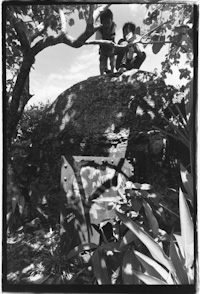

But, what you see instead is an endless blue surrounding a steamy saturated deep green jungle, clear blue skies, sudden tropical black-flash storms, and clouds piling up against an island mountain peak. Quiet dense rain. The sun. Palm trees. Burrowing crabs. Families zipping around from island to island in their little fiberglass boats. Brown dogs and laughing kids playing on the beach.

And divers.

Indeed, diving seems to be the major industry on this island outpost--that and the sale of outboard motors. Little boats are constantly leaving the dive shop, crisscrossing the lagoon for easy day trips. There are liveaboards always anchored somewhere, quietly moving from dive site to dive site. All these boats are full of happy divers, wetsuits, tanks, and smiles. Truk Lagoon is the most concentrated and accessible location for ship wrecks that one could imagine, in any world. This is a Davey Jones themed Disneyland for divers, where, you would think, no expense was spared to please the visitors' eye. In this, it is easy to forget the reality. Behind all the happy smiles and wonder there is a hushed reverence and legal protection for the final resting place of all that perished here. Hidden just below this lagoon is a graveyard.

Here and there on the islands, clues can be found; a few trophies casually placed around. A couple of machine guns by the dive shop, painted white, look sanitized and artificial in the sun. Others are just a flinty black patina of varnished rusting metal burnished into faintly recognizable weapons, twisted by time into post-apocalyptic shapes. Up in the hills, dug in and hidden under an ominous green canopy, are the big guns, sleeping wherever thunder goes to dream.

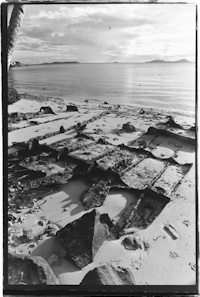

But, anywhere, if you look, each step could put you on some stranded fragment of broken concrete, rusting metal, cut stone, or memories reclaimed by the jungle, and eaten by the sun and salty air. The organism of life itself constantly, ongoing, encompasses the old, taking new shapes, new uses--a machine gun nest, now just a mound on the lawn, the foundation of some burned out building, now a pen to hold the family pig.

A small launch is tied off at the ragged end of the dock to a piece of rusted metal. Looking closer, almost lost in the sand and nearly rotted away, is another large machine gun. Looking more like a skull strung together with a chain of partially buried bones--it may well be that people have been tying their boats to this dead weapon for over sixty years.

Then there are the wrecks.

Sticking out of the sand, on the edges of the water, waiting in the shallows, you can find clues they must exist. An airplane wing, or what used to be a useful ribbed structure. A heavy diesel engine. Shreds of a collapsed vessel, perhaps a barge. A glimmer of some shape below the waves, an unnatural pattern of light and dark against the sand.

Given time, your imagination would eventually lead you out into deeper water. Even if no one told you they were there, you would look for them. You would know, beneath this sea, buried and out of sight, there waits this other world: a sunken graveyard for the arts of war.

Maybe you would just snorkel out for a casual look. Or maybe you'd get more serious. For over forty years, divers have been letting their curiosities lead them. At the bottom of this lagoon lie scores of sunken cargo and support ships commandeered for the Japanese war effort: military vessels, a submarine, destroyers, fighter planes, bombers, and the lost lives of hundreds of men.

And, so, we find ourselves with doubles and sling bottles, and bright big lights, following the lead of Jacques Cousteau, Al Giddings, Sylvia Earle, Klaus Lindemann, the immortal guide, Kimiuo Aisek, and all the thousands of other divers who have heard the siren call and headed for the bottom.

And, what do you see when you drop down?

If the wreck is intact, upright and sitting in shallow water, you might recognize the whole thing, even before dropping over the side. It can't be right, you say. This can't be real--like something Nemo might have left. The hint of one of these structures stretches out below the surface. There is a mast, a pilot house--the kinetic architectural mass--the curves, and flowing geometric patterns that spell out "ship;" its magnificent entirety seen looming below the surface. This is the essence of adventure.

Or following the line down much deeper, one might discover a sloping plain broken up by outcroppings of sponges and coral, your light bringing to life every electric candy color before you, beckoning, calling. Small fish weave between a craggy hiding place for octopus. The scene, a peaceful rocky rise in the faint, dancing blue-grey light, is filled with so many sparkling things.

Moving back, scanning; the realization comes into focus--the randomness no longer random--you have landed on the huge hull of a freighter rolled over on its side. You can make out the ship's smooth belly almost exposed, draped masts pointing across the sand, the props just an obscuring swirl of ocean life. What were once walkways, where sailors looked down on busy decks, are now vertical shafts, chasms of non-reflecting black rust cutting stark holes completely through the ship, slicing through to sand.

Almost ornamental, deck guns are frozen and overgrown with color.

It is so easy to be moved along in the spirit of discovery, wonderment, and the fantasy playground of zero gravity. Suspended over an open cargo hold, then following a passageway from one end of a ship to the other, catwalks lead down into engine rooms.

For a moment, you could believe these ships just landed here, got tired of all the strife and tension in the world above, settled in and quietly fell asleep. You could imagine the old steel leviathans peacefully floating down, touching gently on the sand, their engines shuddering to a full and complete stop, their running lights silently fading, winking out. Lifeless. Forever.

Retired, content now; these mighty ships resolved to be the quiet background in the big aquarium around them--a centerpiece for bands of circling sharks--peaceful in their slumber.

Again, while swimming along the sand, with the panoramic expanse of ship

stretched above in all directions, a gaping hole appears--a through and through strike of tangled metal. This was war, after all. The fatal blow that sank this ship is now a ragged arch big enough for us all to swim through.

There is daylight visible from the other side.

Whips of coral play with twisted metal. A patrolling school of barracuda flash silver going by. A pair of jacks edged with glowing blue cross effortlessly before us.

All the tools to build a town are here, lying on the bottom. There are countless man hours invested, and untold fortunes spent to no good end. The most simple and common place of things are here, idling into rust. There are cars, trucks, the famous steam roller, generators, lighting, cables, wire, complete machine shops, a hold full of chain link fencing, toilets, stacks of dishes, crates of beer, and scattered sake bottles. And the empty soles of soldiers shoes.

Next to them are the tools of war, the tanks, the deck guns, the

explosives, the artillery pieces on wheels, shells of all sizes, depth charges,

fighter planes, torpedoes.

The San Francisco Maru sits upright, just as they described her. A single propeller nearly buried completely in the sand; she sits with army tanks spilling off her foredecks, her rear holds full of carbine clips. There are pallet loads of ammunition piled up everywhere. Each single piece is a potential death. Stacked full.

All these things are here, being consumed by the relentlessness of life, overgrown and slowly being eaten by the very sea itself.

Some of the most beautiful propellers are on a ship built in New Zealand. Commandeered and renamed by the Japanese for the war effort, she was born with two three-bladed props, once driven by shafts shrouded in the most graceful curves of Art Deco steel; sculpted, flared, and clad to form the stern. Even veiled with life, they look drafted with an artist's airbrush, built and shaped like a streamliner, locked forever, an inspired gesture captured in timelessness at the bottom of the sea. For a ninety-year old freighter, a most elegant superstructure rises up from these rear decks. But, the entire front end is abruptly gone. The pilot house hangs precariously, teetering over a jungle of madly twisted ship stuff, blindly surveying a field of splayed out ribbing and metal plates scattered across a colorful ocean floor. A violent and horrific explosion once ripped this ship apart and took its living crew of men to the bottom with her death. The bow stands alone, stranded at a distance in the sand. A hundred feet of inside out and collapsed steel separate it from its home.

Wreck after wreck, a pattern emerges. A quick study course in naval architecture. A bow to stern survey. A detailed dive with penetration. Or, the easy stuff, the holds. A passageway with quarters. A galley. The engine room. Deck level after deck level. The light through open skylights. The

breach in the hull. The ship itself.

The line of the bow.

The cut of the stern.

Nothing tells the story better than these two elements. Nothing captures the life and mission of a ship more than a picture of the bow or the stern. Sitting on the bottom in the chapel of this moment, one could look for hours, at either end, absorbing, trying to comprehend all of what this means--the shipness of this place, the silence, the bow arching above, frozen, or the propellers settled in the sand, pushing off to nowhere.

What distant wrenching brought this ship to this place? What horrible ringing is now quiet? The moment is sensed when life leapt from these men and poured out from these ships, and brought them to rest in this faraway twilight place.

Now walls and walls of growth rising up from the sand, festooned cables and masts, some outrageous nautical parade, soundless without music. A glimpse of a Napoleon wrasse, in his own parade. Close in, the small fish everywhere. Clown fish from every circus. Parrot fish. A ray. Swimming the length of the ship, a solitary silvertip prowls the sand.

The last dive, slowly following the mast up, a careful circling to catch and see and remember every last detail--each soft coral, each anemone, each pink tunicate, a naked beating heart.

Good bye.

Catching the anchor line up, two batfish follow--more like silly hats with eyes than fish. Their mouths open, waiting for food, they linger into my twenty foot stop.

They say good bye.